Megan Herrold is a pastoral intern at Resurrection Covenant Church in Chicago. She is currently pursuing an MA in Christian Formation at North Park Theological Seminary, and is the seminary’s student representative on the ECC Commission on Biblical Gender Equality.

I’m not sure, but I might be a beneficiary of affirmative action.

I’m not sure, but I might be a beneficiary of affirmative action.

Last spring I was awarded an internship stipend from the ECC to help me meet the field education requirements for my degree program at North Park seminary. I knew about this grant opportunity, knew there was money available, and was repeatedly encouraged to apply for it, but I was still hesitant to do so. Why? Because the grant was for women in ministry, and I felt strange asking for—or accepting—extra “help” because I’m a woman.

The weird thing is, I don’t have a problem with affirmative-action programs in general. (And I’m not saying that this grant is one.) I know people sometimes think of them as giving new unfair advantages to certain groups, but I’ve always understood them as an effort to counteract unfair disadvantages that already exist in our society. I still go back to this quote from Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., written more than 50 years ago:

The nation must not only radically readjust its attitude toward the Negro in the compelling present, but must incorporate in its planning some compensatory consideration for the handicaps he [or she] has inherited from the past. It is impossible to create a formula for the future which does not take into account that our society has been doing something special against the Negro for hundreds of years. How then can he [or she] be absorbed into the mainstream of American life if we do not do something special for [her or] him now, in order to balance the equation and equip him [or her] to compete on a just and equal basis?

So yes, I believe work should be done to dismantle structural disadvantages and yes, I believe there are unfair disadvantages experienced by women pursuing a call to ministry. So I completely support the idea behind setting aside a grant or other funds to help women (or anyone else who faces extra obstacles) pursue their call.

There’s a young woman in a church I used to attend where I knew her as a teenager. Moving from urban Chicago to the rural Midwest for college was the first time she experienced significant, blatant racial discrimination. She eventually ended up transferring for many reasons, but racism was definitely one of them. Knowing that there are places in this country where college students of color aren’t fully welcome or don’t feel safe is pretty much all the justification I need for the fewer universities that are more welcoming to allow affirmative action to influence their acceptance policies.

Similarly, in one of my first meetings with an internship advisor where I mentioned possibly wanting to do an internship in the southern U.S., I was explicitly told that there are churches in that area to which he tries not to send women because women in those places won’t receive as much encouragement in their call. So just as in the last story, knowing that women aren’t welcome as ministers in all churches in our denomination is, in my mind, justification for financial resources that help women find an internship in the fewer places where they are welcome to serve.

But it still feels weird for me to accept help. And it definitely feels weird to accept something I feel like I didn’t do anything to earn. Which contradicts one of the ideas I often hear about affirmative action, this idea that some people are just looking for any advantage they can get, or just want special treatment. I’ve honestly never understand this perspective. To accept extra assistance because you’re part of a disadvantaged group means acknowledging that circumstances are stacked against you. Who would want to think about their life that way? I know I wouldn’t.

I recently finished reading The Fire This Time, a collection of essays about race and racism in the U.S. One of the essay writers, Rachel Kaadzi Ghansah, shared some of her feelings about being “the first black intern” at a magazine that was more than 150 years old at the time of her internship in 2005:

I became paranoid that I was merely a product of affirmative action, even though I knew I wasn’t. I had completed my application not once but twice and never did I mention my race. Still, I never felt like I was actually good enough. And with my family and friends so proud of me, I felt like I could not burst their bubble with my insecurity and trepidation.

I don’t think anyone wants to believe that these kinds of assistance programs are necessary. Not even those who might benefit from them.

Here’s where I want to have some concluding thoughts, a nice summary to wrap up all this conflict. But the truth is that I’m still conflicted. I haven’t yet figured out what I think or feel about this. Am I at a disadvantage as a woman in ministry? Am I justified in accepting assistance? Once I accept it, is it fair that I feel extra pressure to work harder, more, better, in order to earn it, to prove that I’m worthy of help? How does it affect me as a pastor to face all of these questions in the midst of ministry?

These are the thoughts I’ve been wrestling with the last few months as I think about this fortieth anniversary of ordaining women in the ECC and what it means for me to be a pastor today. This is the legacy I’ve inherited. How do I accept it, and what do I do with it?

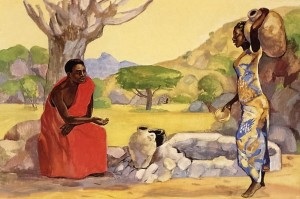

It is all very scandalous really…she is a ridiculed woman and left out of her community. She, a Samaritan of not “pure” bloodline speaks with a Jewish rabbi alone. And Jesus and this woman converse, she gives him water and he gifts her with the knowledge of his gift of grace and life…of living water.

It is all very scandalous really…she is a ridiculed woman and left out of her community. She, a Samaritan of not “pure” bloodline speaks with a Jewish rabbi alone. And Jesus and this woman converse, she gives him water and he gifts her with the knowledge of his gift of grace and life…of living water.