CHICAGO, IL (November 21, 2006) – Shane Claiborne appears in the Evangelical Covenant Church’s 24/7 curriculum that recently began distribution through Zondervan Publishing.

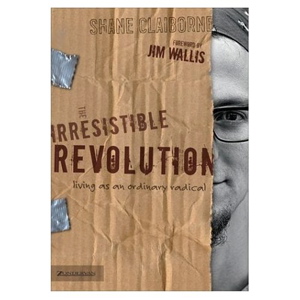

The company also has published Claiborne’s new book, Irresistible Revolution, which calls on Christians to live as “ordinary radicals.” To read more about the new curriculum, please see 24/7 Experience. To purchase a copy of Claiborne’s earlier book, please see Irresistible Revolution.

Inspired, Claiborne and a friend traveled to Calcutta, India, and worked for 10 weeks among lepers alongside the late Mother Teresa (Claiborne calls her “Momma T”). He then spent a year as an intern at one of the United States’ largest megachurches, Willow Creek, located in an upscale area of suburban Chicago. For the past 10 years, Claiborne, who is 31, has lived communally in the Kensington neighborhood of Philadelphia – considered by many the city’s most violent area.

Inspired, Claiborne and a friend traveled to Calcutta, India, and worked for 10 weeks among lepers alongside the late Mother Teresa (Claiborne calls her “Momma T”). He then spent a year as an intern at one of the United States’ largest megachurches, Willow Creek, located in an upscale area of suburban Chicago. For the past 10 years, Claiborne, who is 31, has lived communally in the Kensington neighborhood of Philadelphia – considered by many the city’s most violent area.

The community, known as The Simple Way, has the vision of loving the people of the neighborhood, working to promote non-violence and creative peacemaking initiatives, and improve the living conditions of those in the neighborhood.

He has been featured in Christianity Today as a leading voice in what has been called the new monasticism, comprised of intentional communities from around the country. Covenant News Service interviewed Claiborne by telephone.

What was it like doing the 24/7 video?

I loved doing it. It was a blast. There are people still talking to me about the video.

How did you develop your views on non-violence and peacemaking having grown up in a very conservative, traditional church in eastern Tennessee?

Most of my theology of non-violence and peacemaking comes from living in a neighborhood that is haunted by a lot of violence. It didn’t come from just reading good theology. Those things inform each other.

After waiting several weeks for a response to a letter you sent seeking permission to work alongside the Sisters of Charity in Calcutta, India, you called, and Mother Teresa answered the phone. What was that like?

It was really cool to see she was just an ordinary person. I didn’t feel like I was asking the right questions even though the questions I was asking were very logical: Where are we going to stay? What are we going to eat? She just said, “Foxes have holes, birds have nests, but the son of man has no place to lay his head.”

How did that experience influence the values of your current community?

It’s like Mother Teresa said, “We can do no big things, but only small things with great love.” So we try to stay true to the small things when everyone around us has these great visions and are out to change the church. While I’m for those things, we can only get there by doing the small things. God’s getting us ready for something really, really small.

Monasteries were started as a reaction to a church that had lost its way and viewed as having sold out to society’s values. What role does the new monasticism play?

One thing I would say as sort of a precursor is that I don’t spend a lot of time talking about new monasticism and the movement, because that can become very narcissistic. I love talking about community.

It’s helped us to locate ourselves within church history, to see this isn’t something new or extraordinary. Over and over – and often in the most confusing times of history – when all sorts of things are being done in the name of God, groups of people have pulled away to rethink what it means to be Christian, to ask how do we fuse right believing and right practice.

And that’s something that I would critique of other movements that are going on now, like you see with postmodernism or the Jesus people of the 1970s. Many of them pulled themselves out of the traditional and ancient congregations and communities. You end up with a sort of pretension that we’re going to do this better than you. This is at odds with the church rather than seeing it as a renewal of the church. So we don’t plant churches everywhere, and we don’t see ourselves as postmodern churches. We see ourselves connected with the larger church.

You talk about activism versus a community operating out of love. What do you mean by that?

Believers and activists are a dime a dozen, but lovers are hard to come by. You can hand out signs like we can hand out tracts – completely without any relationship or any love. What we really need are people committed to loving their neighbor as they love themselves. What we really need is some longevity, living in a neighborhood that is struggling.

I was at Princeton and everyone was asking what issues we should get involved with. I said don’t choose issues, but choose a group of people you want to come alongside, maybe a group of people who have been pushed out or ostracized. The issues will rise out of those relationships. They need to come out of that, rather than just reading.

I was at Princeton and everyone was asking what issues we should get involved with. I said don’t choose issues, but choose a group of people you want to come alongside, maybe a group of people who have been pushed out or ostracized. The issues will rise out of those relationships. They need to come out of that, rather than just reading.

How hard is it to keep from just being rebellious?

For me, it’s getting easier and easier because it was very tiring to continually speak against things and not have any solutions. Just protesting was tearing down, but not having anything to build. People watch protests on the news and speaking out against stuff, but most people know things are not right. We’ve had a sort of paralysis of imagination to imagine what things could look like.

I am incredibly energized by the movement in our community, where we’re pouring our energy into constructive alternatives that are marks of a new society. It’s more magnetizing than the other.

You say churches should act with more imagination. How can churches begin to foster that imagination when they are used to acting in the same ways over the years?

I think the big part of it is getting outside ourselves and learning from others that are different from us, from other cultural backgrounds and other economic strata. We have a lot to learn from each other. It makes for a rich life. As we think and learn from each other, all kinds of things are born out of that because we celebrate each other’s gifts, and we recognize each other’s weaknesses. There are a lot of young people who have a lot of imagination, so we really need to celebrate the imagination of our youth.

You clearly disagree with Willow Creek about some of its decisions, but you speak with such respect for Bill Hybels. How are you able to do that when it can be so fashionable for people to be judgmental about the megachurch?

I love and learn a lot from Willow, and they’ve contributed a great deal to my own spiritual formation – both from things I learned directly and from things I disagreed with.

I think that’s where folks at Willow see what we’re doing and that we are trying. There are definitely places where we read the scripture differently, but there are so many people at Willow who are after the same God and the same gospel.

Is it possible to live fully as a Christian in the suburbs?

That’s a question I get all the time. There are good things in almost any subculture. The suburban life has some beautiful things. There was an inner city town meeting where everyone was criticizing white middle class values and how horrible the gentrification was, and this woman spoke up and said, “They’re not all bad. We want kids eating better, we want kids to have a dad and a mom, and we want to have places where our kids can play in the grass.”

There are things to affirm about it, but there are also so many things about it that collide with the kingdom of God. There are ways we gate ourselves in. We separate ourselves from dependence in community, and so we wind up having values that reflect the society rather than the kingdom of God. We value independence and things that are in conflict.

We really have to cut through the suburban bubble. But it’s changing, I think. There are ways I think we have to tear down the walls with our neighbors. Try creative things. Do laundry at each other’s house. Not everyone needs to own a washing machine or a lawnmower. There are people who are experimenting with community gardens.

I think its really difficult to appreciate God’s love and God’s grace when we’re not alongside people have who have suffered deeply and know that well. And there are certainly people in the suburbs that are poor in spirit.

You went to Iraq and were there when the bombing started as part of the shock and awe campaign. How can we engage in creative peacemaking in a place where a hundred bodies a day are being dumped on the streets?

I think one thing we can learn from what we’ve experienced is not allow history to repeat itself. It’s not looking good that we can bring peace through the sword.

A friend of mine just got back from Lebanon, where so many buildings have been reduced to rubble. The folks there have hung banners that say, “Made in the USA.”

I think that there are ways we can be the church. A number of us have been in Palestine and learned that there are more Palestinian Christians than there are Israeli Christians. We can begin to learn how to develop an identity with brothers and sisters in Christ that run deeper than nationalism.

A friend of mine went to Palestine and got to know some Palestinian Christians and helped them set up a tee shirt business. They’re now employing 90 Palestinian Christians to make sure each of the workers are treated with respect and the shirts are being fairly traded.

What is justice to you?

Justice is very close to that idea of righteousness – that things are put into place in the way that God wanted them. That doesn’t always mean that it’s just about everyone getting what they deserve. You can have punitive justice – an eye for an eye, you break my arm I break your arm, you bomb me, I bomb you. What’s distinct about Christian justice is that we also believe in reconciliation and grace and restored relationships.

What does your family in Tennessee think of what you are doing?

Well, my dad died when I was seven, but my mom and I have always been very, very close. It’s been a wild ride for her. She has always been very courageous to get out beyond her bubble of theology. It’s been incredible.

We’ve had families coming out of domestic abuse go down and stay with her. It’s opened up new possibilities for her to where she’s saying, “Maybe I can do this where I am.” When I was going to Iraq, she said, “I used to pray for your safety. Now I’m not sure that is the best thing to pray, but I pray that you will be with God.”

My stepfather is a builder, and I called him one time because we wanted to get a roof for a neighbor and I wanted to see what a fair estimate was so we didn’t get ripped off. He got in a car and drove 11 hours up here and we worked together on her roof. They’re always surprising me with how supportive they are, how hungry they are to do what God would have them to do.